Overview

Endocarditis

Endocarditis

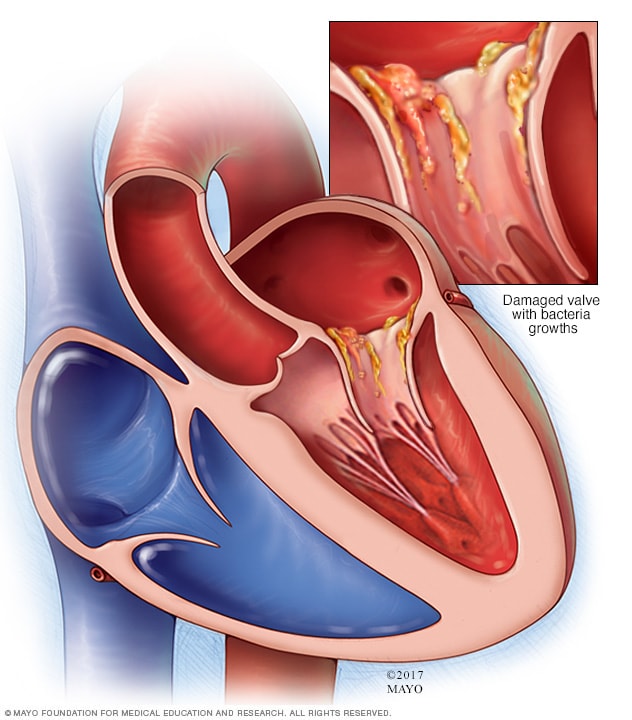

Endocarditis occurs when bacteria or other germs enter the bloodstream and travel to the heart. The germs then stick to damaged heart valves or damaged heart tissue.

Endocarditis is a life-threatening inflammation of the inner lining of the heart's chambers and valves. This lining is called the endocardium.

Endocarditis is usually caused by an infection. Bacteria, fungi or other germs get into the bloodstream and attach to damaged areas in the heart. Things that make you more likely to get endocarditis are artificial heart valves, damaged heart valves or other heart defects.

Without quick treatment, endocarditis can damage or destroy the heart valves. Treatments for endocarditis include medications and surgery.

Symptoms

Symptoms of endocarditis can vary from person to person. Endocarditis may develop slowly or suddenly. It depends on the type of germs causing the infection and whether there are other heart problems.

Common symptoms of endocarditis include:

- Aching joints and muscles

- Chest pain when you breathe

- Fatigue

- Flu-like symptoms, such as fever and chills

- Night sweats

- Shortness of breath

- Swelling in the feet, legs or belly

- A new or changed whooshing sound in the heart (murmur)

Less common endocarditis symptoms can include:

- Unexplained weight loss

- Blood in the urine

- Tenderness under the left rib cage (spleen)

- Painless red, purple or brown flat spots on the soles bottom of the feet or the palms of the hands (Janeway lesions)

- Painful red or purple bumps or patches of darkened skin (hyperpigmented) on the tips of the fingers or toes (Osler nodes)

- Tiny purple, red or brown round spots on the skin (petechiae), in the whites of the eyes or inside the mouth

When to see a doctor

If you have symptoms of endocarditis, see your health care provider as soon as possible — especially if you have a congenital heart defect or history of endocarditis. Less serious conditions may cause similar signs and symptoms. A proper evaluation by a health care provider is needed to make the diagnosis.

If you've been diagnosed with endocarditis and have any of the following symptoms, tell your care provider. These symptoms may mean the infection is getting worse:

- Chills

- Fever

- Headaches

- Joint pain

- Shortness of breath

Causes

Endocarditis is usually caused by an infection with bacteria, fungi or other germs. The germs enter the bloodstream and travel to the heart. In the heart, they attach to damaged heart valves or damaged heart tissue.

Usually, the body's immune system destroys any harmful bacteria that enter the bloodstream. However, bacteria on the skin or in the mouth, throat or gut (intestines) may enter the bloodstream and cause endocarditis under the right circumstances.

Risk factors

Chambers and valves of the heart

Chambers and valves of the heart

A typical heart has two upper and two lower chambers. The upper chambers — the right and left atria — receive incoming blood. The lower chambers — the right and left ventricles — pump blood out of your heart. The heart valves, which keep blood flowing in the right direction, are gates at the chamber openings (for the tricuspid and mitral valves) and exits (for the pulmonary and aortic valves).

Many different things can cause germs to get into the bloodstream and lead to endocarditis. Having a faulty, diseased or damaged heart valve increases the risk of the condition. However, endocarditis may occur in those without heart valve problems.

Risk factors for endocarditis include:

- Older age. Endocarditis occurs most often in adults over age 60.

- Artificial heart valves. Germs are more likely to attach to an artificial (prosthetic) heart valve than to a regular heart valve.

- Damaged heart valves. Certain medical conditions, such as rheumatic fever or infection, can damage or scar one or more of the heart valves, increasing the risk of infection. A history of endocarditis also increases the risk of infection.

- Congenital heart defects. Being born with certain types of heart defects, such as an irregular heart or damaged heart valves, raises the risk of heart infections.

- Implanted heart device. Bacteria can attach to an implanted device, such as a pacemaker, causing an infection of the heart's lining.

- Illegal IV drug use. Using dirty IV needles can lead to infections such as endocarditis. Contaminated needles and syringes are a special concern for people who use illegal IV drugs, such as heroin or cocaine.

- Poor dental health. A healthy mouth and healthy gums are essential for good health. If you don't brush and floss regularly, bacteria can grow inside your mouth and may enter your bloodstream through a cut on your gums. Some dental procedures that can cut the gums also may allow bacteria to get in the bloodstream.

- Long-term catheter use. A catheter is a thin tube that's used to do some medical procedures. Having a catheter in place for a long period of time (indwelling catheter) increases the risk of endocarditis.

If you're at risk of endocarditis, tell your health care providers. You may want to request an endocarditis wallet card from the American Heart Association. Check with your local chapter or print the card from the association's website.

Complications

In endocarditis, irregular growths made of germs and cell pieces form a mass in the heart. These clumps are called vegetations. They can break loose and travel to the brain, lungs, kidneys and other organs. They can also travel to the arms and legs.

Complications of endocarditis may include:

- Heart failure

- Heart valve damage

- Stroke

- Pockets of collected pus (abscesses) that develop in the heart, brain, lungs and other organs

- Blood clot in a lung artery (pulmonary embolism)

- Kidney damage

- Enlarged spleen

Prevention

You can take the following steps to help prevent endocarditis:

- Know the signs and symptoms of endocarditis. See your health care provider immediately if you develop any symptoms of infection — especially a fever that won't go away, unexplained fatigue, any type of skin infection, or open cuts or sores that don't heal properly.

- Take care of your teeth and gums. Brush and floss your teeth and gums often. Get regular dental checkups. Good dental hygiene is an important part of maintaining your overall health.

- Don't use illegal IV drugs. Dirty needles can send bacteria into the bloodstream, increasing the risk of endocarditis.

Preventive antibiotics

Certain dental and medical procedures may allow bacteria to enter your bloodstream.

If you're at high risk of endocarditis, the American Heart Association recommends taking antibiotics an hour before having any dental work done.

You're at high risk of endocarditis and need antibiotics before dental work if you have:

- A history of endocarditis

- A mechanical heart valve

- A heart transplant, in some cases

- Certain types of congenital heart disease

- Congenital heart disease surgery in the last six months

If you have endocarditis or any type of congenital heart disease, talk to your dentist and other care providers about your risks and whether you need preventive antibiotics.